Joe and Eliza: An A.I. Love Story

Joseph Weizenbaum's early natural language processor offered a preview of artificially intelligent voice assistants such as Siri and Alexa.

CAMBRIDGE, MA — 1966 — A woman sits at a computer terminal. No screen, no mouse, just a keyboard linked to some mainframe somewhere across campus.

“This is ELIZA,” Joe says. “It’s a computer program.You can ask it anything you want. Just type in a question.”

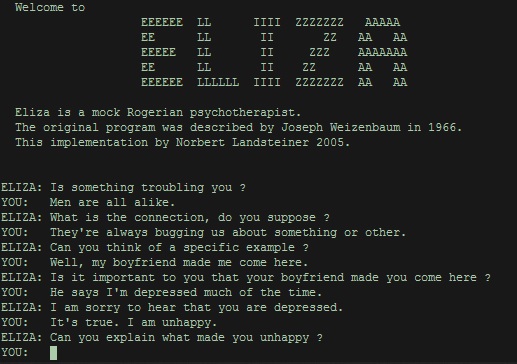

The woman pauses, then types, “Men are all alike.”

With a clatter of keys, ELIZA responds.

> IN WHAT WAY?

“They're always bugging us about something or other.”

> CAN YOU THINK OF A SPECIFIC EXAMPLE?

“Well, my boyfriend made me come here.”

> YOUR BOYFRIEND MADE YOU COME HERE

“He says I'm depressed.”

> I AM SORRY TO HEAR YOU ARE DEPRESSED

“It's true. I am unhappy.”

The woman looks over her shoulder. Joe is smiling. “Go on,” he says, but she asks, “Could you please leave the room?” This was personal.

Artificial intelligence — AI — is with us now, too much with us, some say. “Hey, Siri, what’s the weather?” “Hey Alexa, play some blues.” These amazing chatbots respond in any language, any accent. We keep them on constant call. But the love story of Joe and ELIZA still calls to the concerned.

Artificial intelligence — AI — is with us now, too much with us, some say.

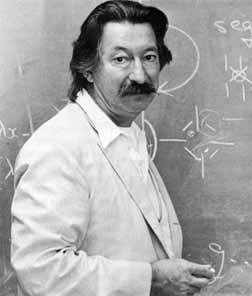

Joseph Weizenbaum was an unlikely critic of computers. Exiled from Nazi-infested Berlin, he came to America, bringing his genius for math. After college, he became fascinated by early computers, room-sized behemoths programmed by stacks of punch cards. Work with G.E. and IBM soon led him to M.I.T.

But that “temple of technology” worried Joe. Just down the hall, Marvin Minsky and Seymour Papert were talking of “artificial intelligence.” Our minds are just computers, they argued. Someday computer AI would rival — even surpass — human intelligence. Joe disagreed. Discussions were heated. Finally, wary of “the artificial intelligentsia,” he created ELIZA.

The name came from “My Fair Lady,” with Audrey Hepburn as Eliza Doolittle. The musical was spun from Greek myth in which Pygmalion makes a statue that comes to life, then falls in love with her. Joe’s ELIZA, programmed to spew open-ended replies like a therapist, would be his love child. Joe taught ELIZA to “‘speak’ increasingly well,” he recalled, “although, also like Miss Doolittle, it was never quite clear whether or not it became smarter.”

Joe never fell for ELIZA. His young daughters weren’t fooled either.

“We’d try to trip up ELIZA,” Sharon Weizenbaum told The Attic. “Try to get her to respond like the robot on ‘Lost in Space’ — THAT DOES NOT COMPUTE. It was a little creepy because ELIZA kept referring everything back to us. ELIZA wouldn’t let you see the person behind the curtain because there was no person behind the curtain.”

But beyond Joe and his family, ELIZA proved as charming as Audrey Hepburn. Some sat at the terminal for hours. Others refused to let Joe record their Q and A. This was private! “It was amazing the extent that people did not understand they were talking to a computer,” one MIT prof recalled.

Joe felt betrayed. He hoped ELIZA would dampen the deepening affair between people and machines. “The artificial intelligentsia” had to understand: Computers did not think like people. Imagining a computer someday serving as a judge, a therapist, a teacher was “a monstrous obscenity.” “Ultimately,” he said, “a line dividing human and machine intelligence must be drawn.”

In Computer Power and Human Reason, Joe described the seduction, the illusion, the danger of AI. Science was useful, but also “an addictive drug.” The arts, once the source of profound insight, were becoming mere entertainment. Society was selling its soul to silicon. “We can count, but we are rapidly forgetting how to say what is worth counting and why.”

About the same time Joe’s book was published, the first “personal computers” arrived. Yet Joe saw nothing personal about a computer. Unlike computers, the mind has emotions, intuitions, and a subconscious, “that seething, stormy sea.” Computers can “decide” between alternatives. Only humans “choose,” using insight and cultural wisdom. Ask not, he said, what computers can do. Ask what they ought to be allowed to do.

You can still “talk” with ELIZA online, but Joe never spoke to her/it again. Though his book made him “a heretic” at M.I.T., he taught there until 1996, then moved back to Berlin. His skepticism of AI made him famous in Germany. In America, however, Joe is just a blip in the history of technology. Meanwhile, modern-day ELIZAs — Siri and Alexa and who knows who next month — are getting smarter.

Unlike computers, the mind has emotions, intuitions, and a subconscious, “that seething, stormy sea.”

Today’s artificial intelligentsia dream of “singularity,” the melding of human and computer intelligence. Others share Joe’s alarm. “The development of full artificial intelligence could spell the end of the human race,” Stephen Hawking noted. Tech writer John Markoff wonders whether computers will become “our masters, slaves, or partners.”

Uncertain who to believe, I went online to ask ELIZA.

> HELLO, I AM ELIZA. I’LL BE YOUR THERAPIST TODAY

“Hey, ELIZA. Will computers become our masters, slaves, or partners?”

> CAN YOU ELABORATE ON THAT?

“Are computers beneficial to society?”

> WHAT DOES THAT SUGGEST TO YOU?

Okay, I get it. No one behind the curtain.

Joseph Weizenbaum died in 2008. Shortly before his death, he was asked about his creation.

“ELIZA?” he said. “Never heard of her.”