Virginia Apgar, Pioneering Anesthesiologist

Millions of newborn babies have benefitted from her standardized APGAR test to assess their health.

Whether she was bicycling with a colleague’s child, cheering at a baseball game, or taking flying lessons, Virginia Apgar always kept the following things on her person: a penknife, an endotracheal tube, and a laryngoscope, just in case someone needed an emergency tracheotomy. Even when she was off-duty, she was on: “Nobody, but nobody, is going to stop breathing on me.”

Rachel Swaby writes about science and is the author of Headstrong: 52 Women Who Changed Science — and the World (Broadway Books), from which portions of this essay were adapted.

Apgar was one of the earliest medical doctors to take up anesthesiology. She was fast talking and fast thinking, an endless spring of energy. Growing up in New Jersey with an amateur inventor and scientist as a father and a chronically ill brother, Apgar quipped that her family “never sat down.” She didn’t, either. In college, while earning top marks studying for a zoology degree, Apgar churned out articles for her college newspaper, became a member of seven sports teams, acted in theater productions, and played violin in the orchestra. After the stock market crash of 1929 hit her family hard, Apgar picked up a collection of odd jobs, including one catching stray cats for the zoology lab. “Frankly, how does she do it?” asked the editor of her high school yearbook. The question could be applied to any stretch of her life.

As a young doctor, Apgar realized something striking: infants weren’t being systematically examined right after birth.

There were some things she didn’t make time for, namely, bureaucracy and red tape, which she’d walk over if she felt like they were stopping her from helping a patient or doing the right thing. If an elevator frightened a child, she’d scoop him or her up in her arms and take the stairs. During her medical school residency, Apgar worried that she might have made a mistake that contributed to a patient’s decline. She asked for an autopsy, but it wasn’t granted. Uncovering the truth became an irrepressible need, so she snuck in and reopened the incision herself. Apgar immediately reported her error to her superior.

She had no tolerance for insincerity or deception. Her own example of openness — an ability both to admit her failures and to adapt as anesthesiology changed — was instrumental in helping the discipline move forward. In fact, it was her flexibility that got her to anesthesiology in the first place.

When Apgar began her internship in surgery at Columbia University in 1933, she was one of only a few women studying it in the country. She worked under the chair of surgery, who recommended she shift focus and join the emerging field of anesthesiology, which, at that point, wasn’t even considered a medical specialty. For her advisor, the recommendation was self-serving. He admired her abilities and he spotted a need. At the time, if a patient required anesthesia, a nurse stepped in. But as surgeries became more complicated, Apgar’s advisor realized that anesthesia would have to keep pace with highly skilled practitioners talented and driven enough to forge the way in a rapidly emerging field.

Apgar spent a year away from Columbia to train. When she returned in 1937, she laid out a plan for how the Division of Anesthesia would function within the Department of Surgery at Presbyterian Hospital. She asked for a title (director), suggested an organizational structure, and mapped out how to establish residencies and bring in more specialists without displacing the nurses already working in anesthesiology. For eleven years, Apgar headed the division, training medical students, recruiting residents, and doing research. She played a major part in helping the specialty grow, but when the division became a department, a male colleague was given the position of chair.

Apgar turned her focus to babies. While administering gas to women in labor, she noticed a curious lack of data. The statistics she did have were puzzling. Thanks to hospital deliveries, more mothers and babies were living through birth, but for newborns, the first twenty-four hours remained particularly perilous.

When Apgar looked into the issue, she saw something striking: infants weren’t being examined right after birth. Without an immediate appraisal, doctors were missing signs that a baby was, say, starved for oxygen, a factor in half of newborn deaths. Furthermore, Apgar realized that a set of standards to compare newborns against simply didn’t exist. If the mother was given drugs during labor, sometimes her baby would take one breath and not take another for several minutes. Did that count as breathing or not breathing? It depended on the delivering physician. Apgar stated what now sounds like the obvious: a baby shows clear signs when it’s struggling, and all babies should be monitored for these red flags.

How would one go about doing a quick, standardized assessment of a newborn, a medical resident asked Apgar. “That’s easy,” she replied, grabbing a nearby piece of paper. “You would do it like this.”

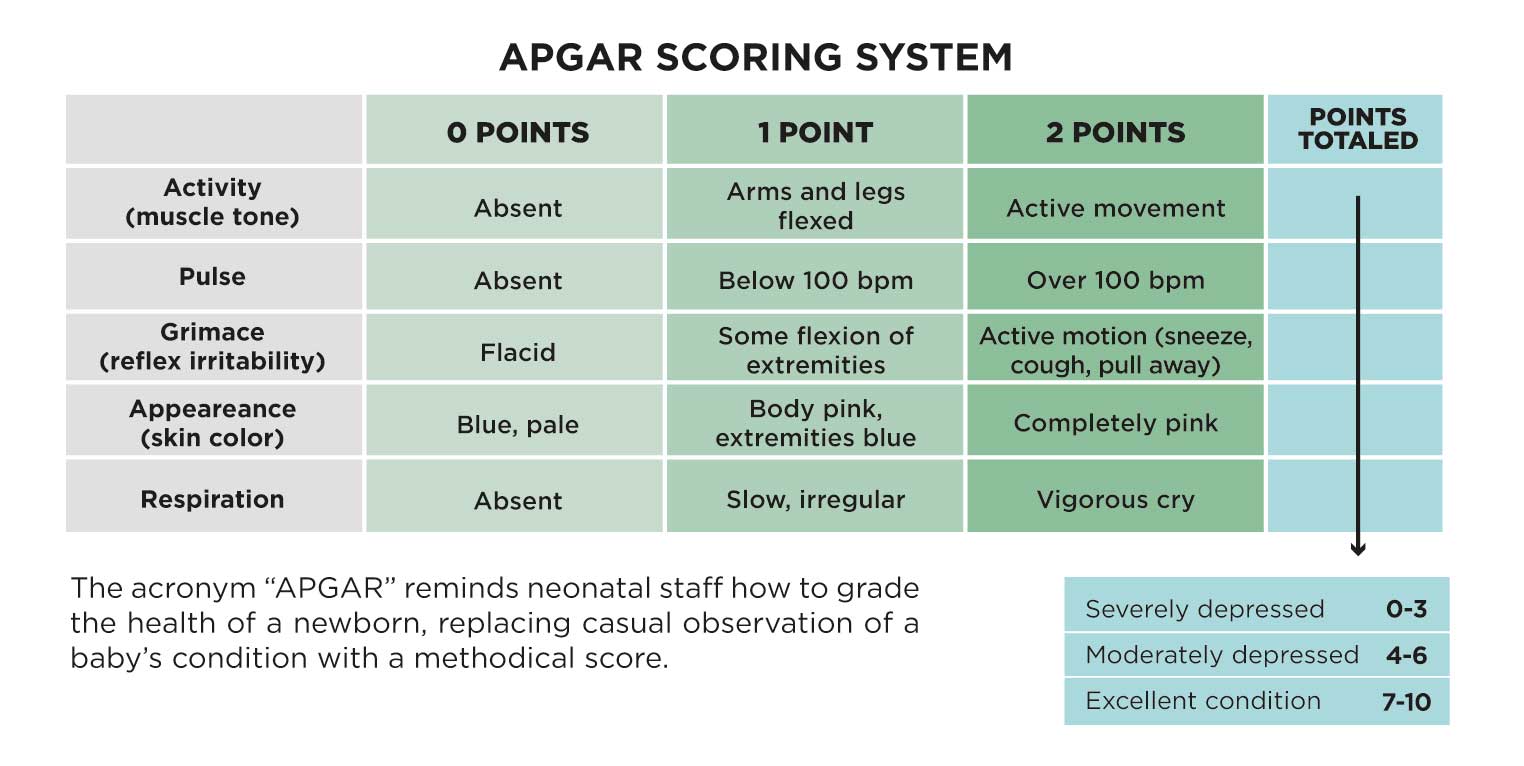

The scoring system would cover five major areas requiring a physician’s attention: heart rate, respiration, reflex irritability, muscle tone, and color. Each was rated on a scale of 0 to 2. Almost immediately, Apgar and some colleagues deployed the system to find connections between scores and a baby’s health. Low scores, they found, send up a signal that there are carbon dioxide and blood pH problems. In the case of an overall score of 3 or less, the baby was almost always in need of resuscitation.

A single baby’s score was powerful, but the effect of analyzing thousands of them was like a field of fallen leaves suddenly organized by color, all these little bits of evidence sorted to reveal their common cause. Lower scores correlated with certain methods of delivery and types of anesthesia given to the mother. Before this small and efficient scoring system, doctors just didn’t see these connections — or didn’t have consistent enough data to prove them. The scoring system became a foundation for better public health statistical models. It began to spread from New York to hospitals across the country. When it reached Denver, the score finally got its famous name. In 1961, nine years after its initial presentation, a medical resident came up with a catchy mnemonic device:

And there it was, the Apgar score. Apgar (the anesthesiologist) loved it.

Meanwhile, data had been pouring in and Apgar didn’t feel adequately equipped to deal with it. Always open to the things that would make her a better doctor, Apgar took a break from her duties at the hospital to pursue a master’s degree in public health. Spotting an opportunity, the National Foundation–March of Dimes swooped in and made her an offer.

Here, as ever, her curiosity drove her decision making. Enticed by the idea of a midlife career change, Apgar finished up her degree and leapt into her new role as chief of the organization’s new Division of Congenital Malformations.

For fourteen years, Apgar flew across the country, spreading information on the reproductive process and trying to dispel the stigma surrounding congenital birth defects. Her quick and witty personality made her a favorite of TV hosts and the patients she visited. As it was often said, she was a “people doctor,” as quick to connect with patients as with viewers and absolutely everyone else she met. “Her warmth and interest give you the feeling that her arms are around you, even though she never touches you,” said one volunteer who worked with her. The foundation doubled its income while she was in a leading role.

Apgar worked with people, flew planes, and cheered for baseball games (her colleagues and friends panting behind her) until her health stopped her. Although she died in 1974, her score is still around. It has protected babies all over the world for the better part of the last century.

Adapted from Headstrong: 52 Women Who Changed Science — and the World by Rachel Swaby (Broadway Books, 2015).